By Lauren Lieberman.

The following excerpt is taken from the Prologue of The Camp Abilities Story.

It was my senior year at West Chester University in Pennsylvania, and

I was volunteering in the Visually Impaired Person (VIP) program run by

Professor Jack Wintermute—“Happy Jack,” as we called him, because he so

clearly loved his work. One weekend each semester he would invite about

twenty adults with visual impairments to campus for recreational activities

such as canoeing, tandem biking, and hiking. College students like me acted

as their guides.

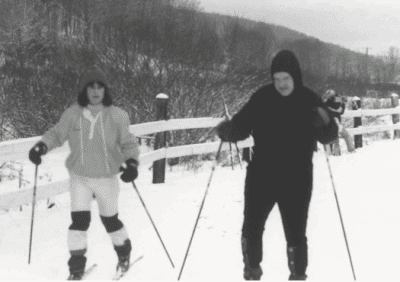

In one of my first classes with him, Happy Jack brought in Sheila, a woman

who was blind, to talk about Ski for Light, a recreation program that originated

in Norway for adults who were visually impaired or blind. After class she

approached me: Would I be interested in volunteering over winter break for

the regional Ski for Light program? I had never cross-country skied, didn’t own

skis, and couldn’t afford to buy them. But of course I said yes!

During orientation, I was expected to learn how to ski, as well as

how to guide skiers who were visually impaired. The training seemed easy

enough, just watching demonstrations . . . until they put blindfolds on us.

This was my first lesson in feeling what it’s like for people who are visually

impaired to master a sport. If skiing blindfolded was scary for me, it must be

infinitely more intimidating for someone who couldn’t take the blindfold off.

It was a lesson in trust.

My guide would shout, “Tips right,” and

I had to trust that there wasn’t a tree or cliff in the way. I had no idea

how steep a hill was until it was too late. I learned later in the weekend

that skiers who were visually impaired could hear the steepness of the hill

by listening to the sounds of the skier in front of them. You can read all

the books in the world about adaptation, but it’s not until you’re actually

forced to confront conditions you can’t see that you fully understand how

much courage and trust is required for a simple slide down a gentle slope.

On one of the first days, I went out skiing with Sally, who was forty-eight

and blind. She had been in the program the previous winter, but

a year’s absence made her nervous on the trails. We moved along the flat

terrain well enough, but when we got to hills, she tightened up. At first,

she had to sidestep down, with extensive verbal and physical assistance

from me. It was slow going, which tried my patience. To me, the hills just

weren’t that big—but then again, I could see them. This was an early lesson

in patience and respect for another person’s level of comfort. I encouraged

her by telling her she was doing a great job each step of the way.

To her credit, Sally kept working on her technique and arm movements,

gliding over the crunchy snow with grace. Soon she was not only getting

the hang of it but actually enjoying it. The next day, we made it around the

trails twice with much more ease and comfort than the day before. When

we got back, we both felt exhilarated. Sally turned to me. “Lauren, I never

could have done this without you.”

I’ll never forget that moment. I was twenty-one and had never received

such deep validation for anything I had done in my life. The feeling that

I could teach someone who is blind to excel at something they had never

done well before was like a drug.

The end of the week was bittersweet. I felt so valued, so much a part of this

world. I couldn’t see it yet, but Camp Abilities was just over the horizon.

I remember thinking at that moment, “I’m going to figure out some way

to do this for the rest of my life.”

To continue reading “The Camp Abilities Story” check out the following links:

Use code XCABP23 for a 40% discount on the paperback version through SUNY Press. Or order the e-book through Amazon.